S.

My Subconscious Jewishness

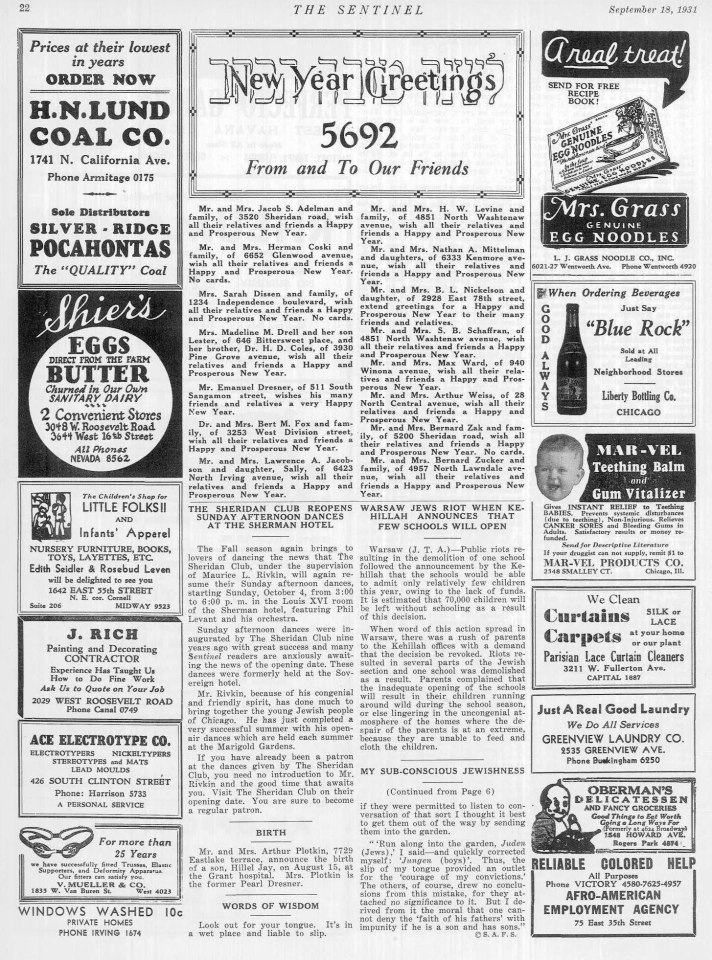

S E P T E M B E R 1 8 , 1 9 3 1

By S I G M U N D F R E U D

E D I T O R ' S N O T E

One of the world's most distinguished scholars and thinkers delves

into the sources of his emotional and intellectual life in order

to understand **Sigmund Freud, the Jew, unless you read these

fascinating lines.**In my childhood I often heard the story that

at my birth my mother’s delight at the new

baby was reinforced by the words of the prophecy

of an old peasant woman, who predicted that I

had brought another great man into the world. Prophecies

of this sort must be exceedingly common; they

express the pride parents feel in their children

and women whose influence on this earth is a matter

of dispute and who look forward somewhat to

the future. Doubtless the prophecies in my case

inspired my mother’s belief in the Jewish

destiny of the race, which may be the source of my long-

ing to know its history.But another impression of my later childhood

casts doubt on the truth of this story. I can tell a

story that has no bearing on this fact. I remember once

in our country house on the Danube we

used to take a nine- or eleven-year-old cousin from

England to dinner. We had a large wooden dining-

table, the commoners’ table, at which the table was placed with some

difficulty at the end of the dining table. I remember that the cousin

looked at the poor table, and he proved grateful to

the dining table for an old wooden stool, which

was near him. What struck my parents was the contented

look on his face. What he said to me as he looked

at the poor table was “Poor table,” which

inspired my mother’s belief in this. I remember that the cousin

had a very peculiar look on his face, which made

a very strong impression on me: a curious, self-

possessed expression. My mother said to me, “Look

how much the cousin has changed in the last few years.

He’s become a real Englishman. I’m quite surprised

that he’s so quiet. I remember that the cousin was

always full of life, and full of fun. But now he is so quiet, and seems

to be absorbed in some secret thoughts.” I remember

the dinner; and the two younger brothers

of the cousin were sitting at the commoners’

table, and they also seemed to be very quiet. I remember

that one of the brothers was sitting next to me. I asked

him if he liked the dinner, and he said, “Yes, I like

it very much.” I remember that he was the youngest

of the three brothers. I remember that he was very

polite, and that he thanked me for the dinner. I remember

that the cousin and his brothers left soon after

the dinner. They were staying at a hotel near

the country house. I remember that my mother

told me that the cousin was studying law at Cambridge,

and that the two younger brothers were studying

at Oxford. I remember that my mother was very proud

of the cousin, and of his brothers. I remember that

she often spoke about them, and that she always

emphasized that they were very intelligent, and

that they were very successful in their studies. I remember

that she often compared me with the cousin, and with his

brothers. I remember that she always said that I was

not as intelligent as the cousin, and that I was not as

successful in my studies as his brothers. I remember

that she often told me that I should study hard,

and that I should try to be as successful as the cousin,

and as his brothers. I remember that she was very

fond of the cousin, and of his brothers. I remember

that she often invited them to our country house. I remember

that they always came with pleasure. I remember

that they always spent a pleasant time at our

country house. I remember that they always left with

regret. I remember that they always thanked my

mother for her hospitality. I remember that my mother

always invited them again.I am very distinctively under the impression that

I, at the time of the impression, I was myself

a child, perhaps about seven or eight years of age, and

I was very much impressed by the cousin’s peculiar

expression. I remember that my mother was very

much concerned about the cousin. I remember that

she often spoke about him to my father. I remember

that she always said that she was afraid that the cousin

was not well. I remember that my father always

tried to calm her down. I remember that he always

said that the cousin was a grown-up man, and that

he knew what he was doing. I remember that my

mother was not convinced. I remember that she often

said that the cousin looked so sad. I remember that

she often said that she was afraid that the cousin was

unhappy. I remember that she often said that she

wished she could help the cousin. I remember that

my father always said that he did not know what

he could do. I remember that he always said that

the cousin was a very private man, and that he did

not like to talk about his personal problems. I remember

that my mother was not satisfied with this answer.

I remember that she often said that she wished

she could speak to the cousin. I remember that she

often said that she wished she could ask him what

was wrong. I remember that my father always said

that she should not do that. I remember that he always

said that the cousin would not like it.I learned from him that he was the son of a

wealthy relative, that he was studying law, and

that he was very interested in the political situation

in England. I remember that he was very enthusiastic

about the Liberal Party, and that he always spoke

with great admiration about the leader of the Liberal

Party, William Ewart Gladstone. I remember that

he told me that he was a great admirer of Gladstone,

and that he considered him to be one of the greatest

statesmen of all time. I remember that he told me

that he had often heard Gladstone speak in public,

and that he had been very impressed by his eloquence,

and by his passionate commitment to Liberalism.

I remember that he told me that he considered

Gladstone to be a true champion of the oppressed,

and that he was very proud to be a member of the

Liberal Party.Given some Jews were included in

the dinner party, the question arose as to what

that boy was carrying. He was carrying a miniature portfolio

in his pocket. I took it for the boy’s indulgence in

a private ritual. This experience

did not help to bring the conversion to the attention

of the cousin. It confirmed that he was Jewish.This is the experience that I must

accept, and it did not help to bring the

conversion to the attention of the cousin. It confirmed

that he was Jewish. I am not lying, and I am not

making up a story. I am only relating the facts as

I remember them. I am only trying to tell the truth.I must have been ten or twelve years old

when my father began to take me accompany him

on his walks. He would take me with him

on the things of this world. Thus, to show meI was hearing Goethe’s beautiful essay on Nature,

and the beautiful essay on Nature was the main

reason for my decision to study medicine.It was a curious experience that

I must have been ten or twelve years old

when my father began to take me accompany him

on his walks. He would take me with him

on the things of this world. Thus, to show me

S I G M U N D F R E U Dhow times had improved since his youth, he

told me, “When I was a young fellow I walked

one day on the street in Freiberg, neatly

dressed up in my best clothes, a new fur

cap on my head. Then a big gentleman came

up to me. He knocked my new cap into the mud

with a single blow. He also called out ‘Go up on the

pavement, Jew!’”“And what did you do?”

“I went off the sidewalk and picked up my

cap,” he said very calmly.To me this did not seem very heroic on the

part of my father, who was recounting this story

to a little boy by the hand. I opposed this

with the example of a much better man,

whose name was my liking - the hero in

a well known story, who was a student at the

university and was studying at the time. This man

had been an arch-enemy of the hero in the story.

The hero had been forced to leave his home. He had

been forced to leave his country. He had been forced

to leave his family. He had been forced to leave his

friends. He had been forced to leave his studies. He

had been forced to leave his whole life behind. He

had been forced to leave everything behind. He had

been forced to start a new life in a foreign country.When he was at the university, this hero, whose

name was my liking, was able to avenge upon the

other hero, in the story, who was the arch-enemy of

the hero in the story, who was the student at the

university and was studying at the time, who had

been forced to leave his home.My parents were Jews, and I have remained

a Jew. It is not an idle belief to believe that my

family settled for a long time in the town

where I was born, Freiberg, in the ninth

century.I was born in the town where my family settled

for a long time.For many years I enjoyed special privileges there.

It was not until I was seventeen, when I entered

the university, that I felt a decisive change.I felt very much alone and very lonely.

My favorite hero during my years at the Gym-

nasium was Hannibal. Like so many boys of

that age I admired him because he was a Roman

rather than with the Romans in the Punic Wars.

My later understanding of the difficulties in the

way to understand the consequences of descent from

the Carthaginians, which was his great-grand-

father, who had been a great hero in the Punic Wars.Animosities among my schoolmasters challenged me to

choose the side of the opposition.

I did notfeel any desire to become a Jew, but the

I was seventeen years old when I entered the

university.I was very much alone and very lonely.

Once I was going home in the evening, after a very

long day at the university, and I was feeling very tired.

I was walking slowly, and I was thinking about my

life. I was thinking about my studies, and about my

future. I was thinking about my family, and about my

friends. I was thinking about my life in Vienna, and

about my life in Freiberg. I was thinking about my

childhood, and about my youth. I was thinking about

my life as a Jew, and about my life as a German. I was

thinking about my life as a student, and about my life

as a man. I was thinking about my life as a human

being, and about my life as a member of society. I was

thinking about my life as an individual, and about my

life as a member of the Jewish community. I was thinking

about my life as a student of medicine, and about

my life as a future physician.I saw the first copies of books in the hands of some

young men. The books were printed in Gothic

type, but I noticed that they had no covers. I looked

at the books, and I saw that they were medical textbooks.

I asked one of the young men what the

books were, and he told me that they were the latest

medical textbooks. I asked him if he was a medical

student, and he said, “Yes, I am a medical student.”

I asked him if he liked his studies, and he said, “Yes,

I like my studies very much.” I asked him if he

thought that the books were good, and he said, “Yes,

I think that the books are very good.”I remember perfectly how these

books brought me some comfort. I remember

the books I was holding, which I had bought from the

young men. The books were printed in Gothic

type, but I noticed that they had no covers. I looked

at the books, and I saw that they were medical textbooks.

I asked one of the young men what the

books were, and he told me that they were the latest

medical textbooks. I asked him if he was a medical

student, and he said, “Yes, I am a medical student.”

I asked him if he liked his studies, and he said, “Yes,

I like my studies very much.” I asked him if he

thought that the books were good, and he said, “Yes,

I think that the books are very good.”That time I remember when

even then my name (the name

which was equivalent of the first mentioned) was my

favorite. Possibly this was due to the co-

incidence that the name was similar to my

birth-date, mine coming exactly a century later.

The hero had been a famous historical personage

in military because his crossing of the Alps

with the Carthaginian army was an event that

changed the course of the world. The military

type may also be explained by the

influence of my mother, who had been fond of

reading, and who had often read to me from the Bible

and from the history of the Jewish people. This

military type may also be explained by the

birth of my two or three children, who were all boys.

I was considerably younger than my mother and

considerably stronger than myself.When, in 1873, I first joined the University, I

was not yet a very good student, and was not yet very

studious.(Continued on Page 22)

S.

(Continued from Page 6)

if they were permitted to listen to con-

versation of that sort I thought it best

to get them out of the way by sending

them into the garden.“Run along into the garden, J U D E N

(Jews),' I said—and quickly corrected

myself: ‘Jungen (boys)’. Thus, the

slip of my tongue provided an outlet

for the ‘courage of my convictions.’

The others, of course, drew no conclu-

sions from this mistake, for they at-

tached no significance to it. But I de-

rived from it the moral that one can-

not deny the ‘faith of his fathers’ with

impunity if he is a son and has sons.”

© S. A. F. S.

6 & 22